Education reform is key to Missouri’s economic success

Two new studies of the state’s education systems and economy paint a clear picture of how underperforming schools (both K-12 and colleges) and the resulting decline in labor force quality have led to a stagnating state economy.

Thankfully, the two studies, coupled with recent research from other states, also describe a clear path for turning around our state’s economic trajectory and bringing up to a trillion dollars in new GDP growth to the state.

Missouri has a stagnant economy

Dr. Timothy J. Gronberg, Dr. Dennis W. Jansen, and Dr. Lori L. Taylor, all of Texas A&M University, argue that Missouri’s worker productivity issues are a result of the state’s failure to keep up with the rest of the country, and some surrounding states, when it comes to college graduation.

“Missouri would be wise to encourage higher enrollment of high school graduates into colleges and universities within the state,” write the authors of the study. “Compared to the nation and to neighboring states, Missouri’s economy has hardly grown over the past 20 years. A key factor here is a lack of commitment by the state to a higher educational system that is capable of producing a sufficient number of college-educated individuals. ”

Increasing college performance key, but difficult to achieve

Gronberg, Jansen, and Taylor encourage the state to consider reversing the current trend of cutting college-level funding and more aggressively using public funds to support higher education as an investment in economic growth for the state.

But, as we wrote last week, increasing college attendance and success also depends on making drastic improvements to our K-12 education system — a system which produces many college freshmen who find themselves unprepared to succeed at the university level (Of the 22,160 high school graduates who enrolled as freshmen in state colleges and universities in 2017, 35.9 percent had to take at least one remedial course).

A growing body of research from across the country is showing that increasing school choice can also lead to higher college attendance and completion rates.

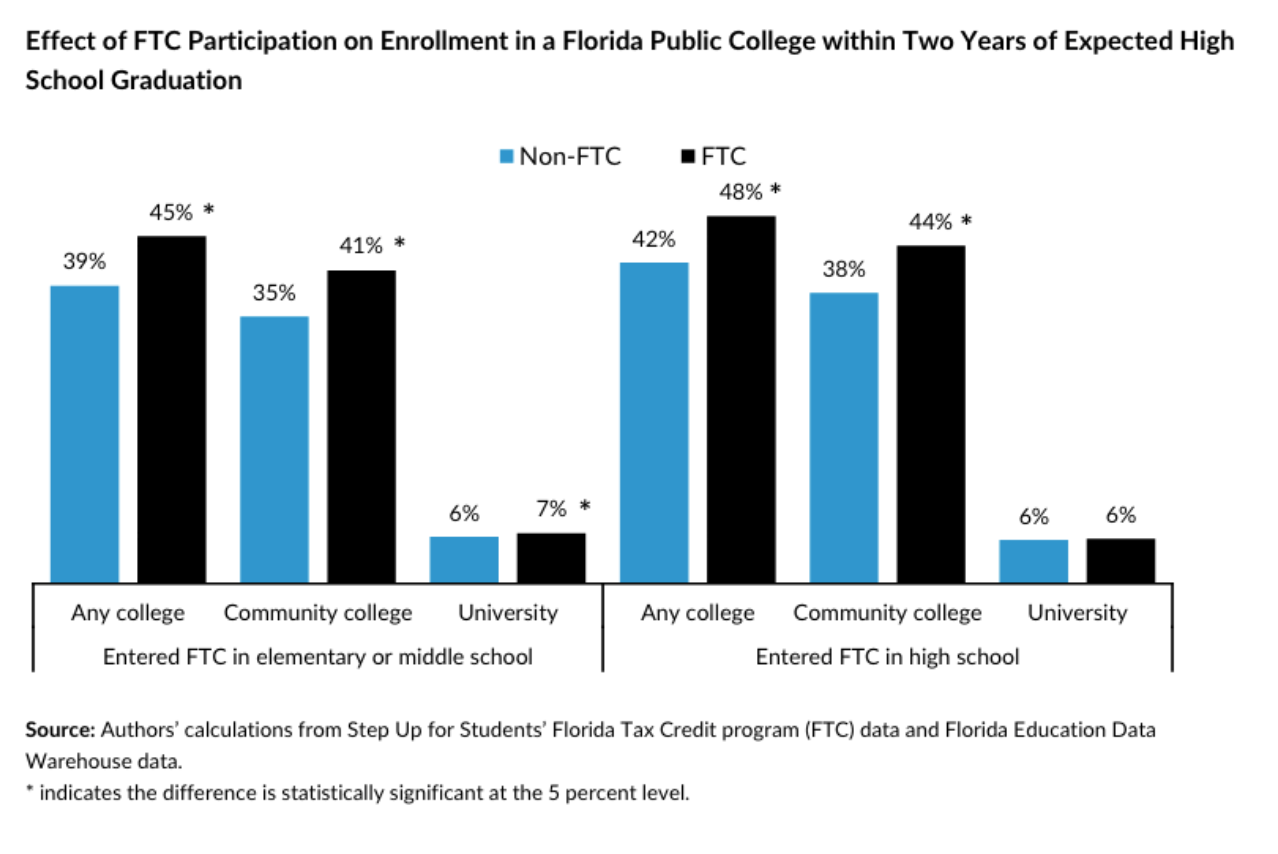

A September 2017 study of the Florida Tax Credit (FTC) Scholarship program, found that low-income Florida students who attended private schools using an FTC scholarship enrolled in and graduated from Florida colleges at a higher rate than their public school counterparts.

A September 2017 study of the Florida Tax Credit (FTC) Scholarship program, found that low-income Florida students who attended private schools using an FTC scholarship enrolled in and graduated from Florida colleges at a higher rate than their public school counterparts.

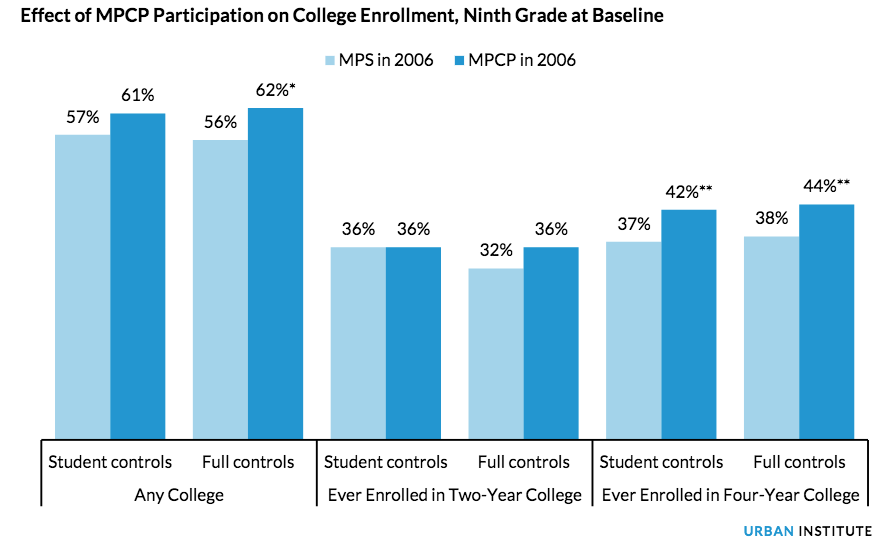

And, most recently, a February 2018 study found that students participating in the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program have greater college enrollment and persistence than their traditional district school counterparts.

And, most recently, a February 2018 study found that students participating in the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program have greater college enrollment and persistence than their traditional district school counterparts.

Improving K-12 access could have big payoffs for the state

“It is clear that Missouri can promote a better economic future for its citizens through educational reform,” writes Hanushek. “The projected gains, based on historical relationships, would not only make the citizens of Missouri better off, but also show how states’ current fiscal problems can be tackled by improving human capital.”

Hanushek’s research shows that bringing all students up to a basic level of performance would yield a present value of added GDP from growth of 1.7 times the current GDP, equivalent to raising the average level of GDP by 3.6 percent above what is expected with no change in school quality.

That simple increase, the lowest level examined by Hanushek, would mean an additional $500 billion in additional economic activity within 10 year’s time. If we were able to raise student performance by one-quarter standard deviation over the next ten years that would result in $786 billion in additional economic activity, and if we were able to match the educational achievement of the top performing state in the region, Minnesota, then we would see over $1 trillion in additional economic activity.

So how do we get there?

“While some argue that the existing changes – charters or accountability, for example – have been too radical, the evidence suggests the opposite,” writes Hanushek “The costs of not improving our educational system in Missouri are extraordinarily large. We have to push harder on the incentives that we know will have positive impacts. Just as importantly, we have to actively consider truly dramatic options. To achieve true change, we must not shy from large changes in parental choice, teacher evaluations and pay, and strengthened accountability.”

« Previous Post: How valuable is a high school diploma

» Next Post: Honoring MLK: Fight for education opportunities, equity