Choice is not a radical idea

If you have followed any of the debate over education policy in the past couple of years then you know there is a contingent of anti-school choice advocates out there who will argue that giving families the freedom to choose the school (or education model) that best fits their children’s needs is part of some nefarious right-wing scheme to destroy public education and society as a whole.

These were actually key talking points during an official training session at the National Education Association Leadership Summit last March.

But the reality is that offering choice is far from a radical right-wing approach to education and actually the way many progressive countries, including the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, and France, provide education.

A new report, The Case for Educational Pluralism in the U.S. by Deputy Director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy Ashley Berner, examines how these systems work in other countries and how they could work in the United States if we could simply escape the century-old confines of defining public education as only being a district school.

Berner argues that in many of these progressive countries the government is only responsible for paying for and regulating, not necessarily providing, education.

As a result, many types of schools are part of the public education system and open for any student to choose to attend based on their needs and beliefs.

As Berner writes, “The Netherlands, for example, supports 36 different types of schools—including Catholic, Muslim, and Montessori—on an equal footing. The U.K., Belgium, Sweden, and Hong Kong help students of all income levels attend philosophically and pedagogically diverse schools.”

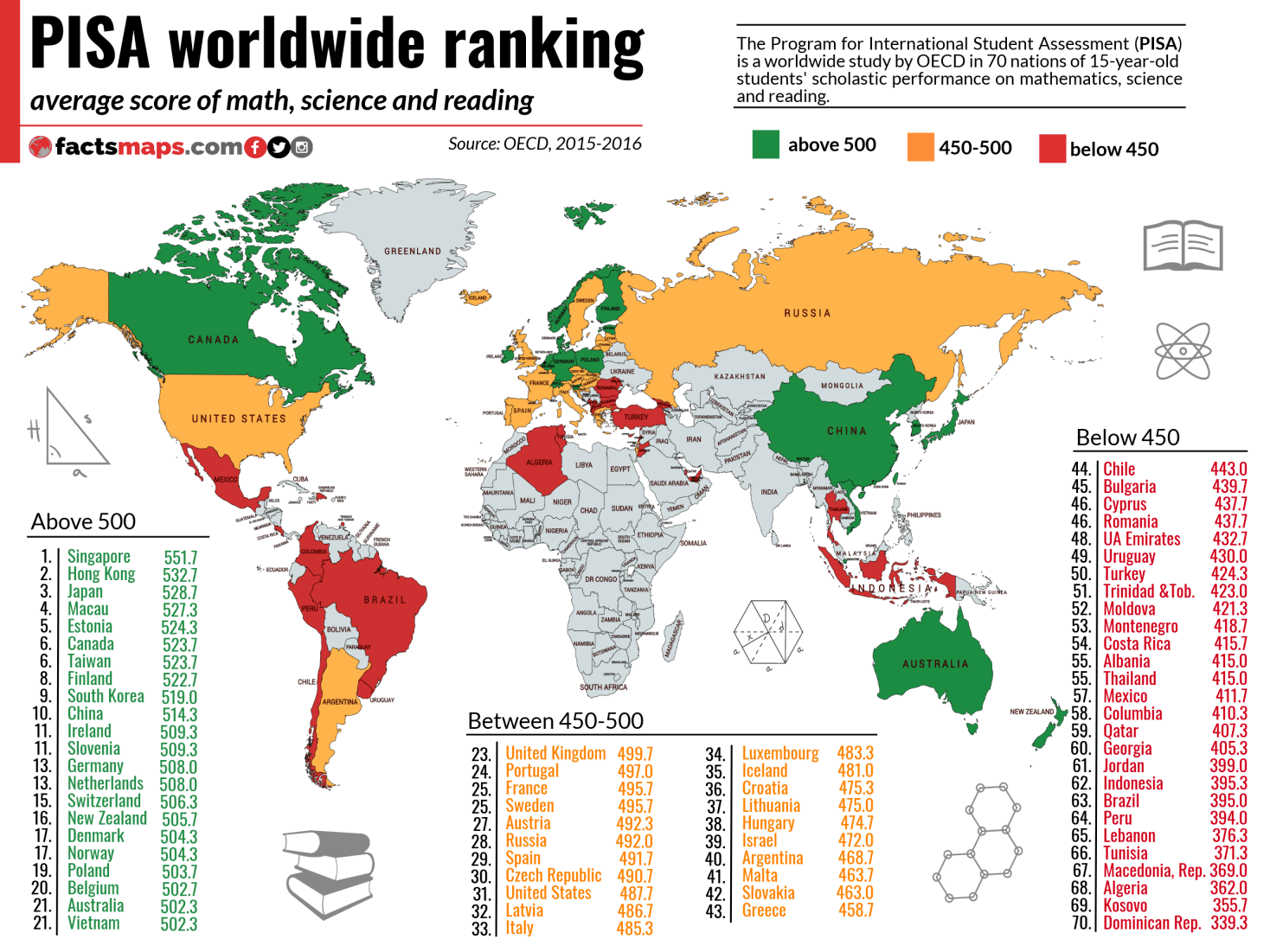

Not unsurprisingly, all of these countries have better educational outcomes for their students than the United States according to the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), a worldwide study by OECD in 70 nations of 15-year-old students’ scholastic performance on mathematics, science and reading.

Berner argues that for a pluralistic system to work, we as a society need to accept five key realities about education:

- The “right school” must be accessible for all families.

- Education is not a neutral enterprise. Schools instruct children, whether explicitly or implicitly, about meaning, purpose, and the good life.

- Education is not merely an individual good but also a common good.

- Education belongs within civil society. In pluralist systems, education is answerable to both the individual and the state—but not exclusively to either.

- Pluralism advances academic and civic achievement.

In practice, these key tenants result in a system where every family can choose the school that is the best fit for their children, both academically and socially. Families can choose a school that matches their values and needs and the government is only responsible for providing the funding for the education and making sure that key elements are taught effectively in every school based on the needs of the society.

This is not a radical idea.

It is, in fact, an idea that may play an increasingly important role in our country’s future as the needs of the workforce change as a result of changing technologies and globalization.

On the PISA rankings, the United States is currently ranked #21 in reading, #32 in mathematics, and #23 in science, which means that other countries are doing a much better job of giving their children the foundation they need to be successful in the 21st-century workplace.

« Previous Post: Homeschooling: Growing and evolving

» Next Post: Missouri loses champion of education